Scanning IP ranges to find friends

tl;dr summary

After a random login to a friend's Minecraft server led us to Shodan, I built a polite IP-range scanner (whois -> nmap -> Minecraft SLP) and piped the results into Elasticsearch + a UI. Scanning ~3M IPs found ~10k servers, plus a reminder to rate-limit, add jitter/backoff, and respect opt-outs.

table of contents

How it started

It all started when a friend of mine who runs a Minecraft server checked the logs and noticed that someone had logged in from an IP address that looked like it belonged to a residential ISP. Curious, we decided to investigate further. When we looked up the IP on shodan.io, we found that it hosted websites for a local high school. This piqued our interest, and we thought it was just a student who had installed Minecraft on a school computer, used Shodan to find the server, and logged in.

Finding out who it was

Then we wondered if there was a way to find out who it was. Looking up his IGN on NameMC didn’t yield any results, so we searched on Google, Bing, DuckDuckGo, and Yandex. We found a chess.com account. He played against his friends, but nothing else.

Using Sherlock, we were able to find more accounts associated with the same username across various platforms but nothing that could help us identify him.

That’s when I had the idea to look in leaked databases, it was a bit desperate (and very unethical) and I didn’t have high hopes, but it worked! We found a first name, a last name, and an email address. Funnily enough, we realized right after that his Minecraft username was a pun based on his real name (and a pretty funny one at that).

So I sent him an email! (translated from French)

Hello [Name]!

I'm reaching out to ask if it was you who connected to my Minecraft server under the username [IGN]?

I'm really curious to know how you managed to get on, especially since it looks like you connected from your high school.

It would be pretty cool if you found it by scanning an IP range!

I hope I'm not barking up the wrong tree here.

Have a great day!

~mollyAnd the next day.. I got a reply!

Hey Molly!

It was probably me who connected to your Minecraft server, since my username is [IGN].

I found your Minecraft server through a website called Shodan (if you don't know it => https://www.shodan.io/).

It's a site that scans the entire internet to find open ports (for example, port 25565 in the case of your Minecraft server).

And I have a question: how did you find my email and that I'm in high school? (From my IP? My Minecraft account?)

Also, could you send me the server's IP again? It's possible I don't have it anymore.

You were on the right track!

And I was a bit shocked to get this email, nice job!

Have a great day!

[Name]We talked a little bit then by email, then Discord and he asked us a lot of questions about computer science, cybersecurity and programming in general, this was extremely wholesome.

This entire experience made me realize that this was the kind of thing I also did for fun when I was a teenager, except that I remained anonymous.

So I decided to build an IP range scanner to find Minecraft servers !

How does it work?

Before talking about the implementation details, let’s go over the general idea.

RIPE IP ranges

I learned recently that the whois command on Linux can not only be used on domain names but also on IP addresses. It queries the RIPE database to find out who owns a given IP address, and in what IP range it is located.

For example, if we run whois 8.8.8.8 (Google’s public DNS server), we get the following output:

NetRange: 8.8.8.0 - 8.8.8.255

CIDR: 8.8.8.0/24

NetName: GOGL

NetHandle: NET-8-8-8-0-2

Parent: NET8 (NET-8-0-0-0-0)

NetType: Direct Allocation

OriginAS:

Organization: Google LLC (GOGL)

RegDate: 2023-12-28

Updated: 2023-12-28

Ref: https://rdap.arin.net/registry/ip/8.8.8.0

OrgName: Google LLC

OrgId: GOGL

Address: 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway

City: Mountain View

StateProv: CA

PostalCode: 94043

Country: US

RegDate: 2000-03-30

Updated: 2019-10-31

Comment: Please note that the recommended way to file abuse complaints are located in the following links.

Comment:

Comment: To report abuse and illegal activity: https://www.google.com/contact/

Comment:

Comment: For legal requests: http://support.google.com/legal

Comment:

Comment: Regards,

Comment: The Google Team

Ref: https://rdap.arin.net/registry/entity/GOGL

OrgTechHandle: ZG39-ARIN

OrgTechName: Google LLC

OrgTechPhone: +1-650-253-0000

OrgTechEmail: [email protected]

OrgTechRef: https://rdap.arin.net/registry/entity/ZG39-ARIN

OrgAbuseHandle: ABUSE5250-ARIN

OrgAbuseName: Abuse

OrgAbusePhone: +1-650-253-0000

OrgAbuseEmail: [email protected]

OrgAbuseRef: https://rdap.arin.net/registry/entity/ABUSE5250-ARINWhat’s interesting here are the NetRange and CIDR fields, which tells us that the IP range for this address is 8.8.8.0 - 8.8.8.255 (or the 8.8.8.0/24 CIDR mask).

This means that any IP address within this range is owned by Google LLC.

So, I took my own IP address, ran whois on it, and decided to run nmap -p 25565 --open -n -oG - <IP_RANGE> on the resulting IP range to find any open Minecraft servers.

I then manually connected to the open servers, some of them had a whitelist, but I was able to connect to a few!

Getting a server’s status programatically

The first thing we need to do after finding a Minecraft server is to get its status. By “status”, I mean the Minecraft server list ping (SLP). It returns the server’s version, players, MOTD, favicon, etc.

It was introduced in Minecraft 1.7. Before that, the client would send a 0xFE packet and the server would respond with a 0xFF packet containing the server’s MOTD and player count. This is not the case anymore, as it was replaced by the JSON status response.

You can find more information about the protocol here: https://wiki.vg/Server_List_Ping

I used an existing Go library for this: https://github.com/dreamscached/go-mc

This is an example of the response (in JSON):

{

"version": {

"name": "1.20.1",

"protocol": 763

},

"players": {

"max": 69,

"online": 1,

"sample": [

{

"name": "Steve",

"id": "..."

}

]

},

"description": {

"text": "Hello world!"

},

"favicon": "data:image/png;base64,...",

"enforcesSecureChat": false

}In reality, most servers don’t have the players.sample field.

I stored this information in Elasticsearch (more on that later) and used it to display the servers in a web UI.

Scanning the IP ranges

Now, we have a list of IP ranges, but how do we scan them?

My first naive approach was to just ping every IP address in the range with the SLP request. This worked, but it was extremely slow and would take days to scan a single ISP’s IP range.

So instead, I used nmap to scan the IP ranges and find any IP addresses with port 25565 open.

nmap -p 25565 --open -n -oG - <IP_RANGE>The -p 25565 option specifies the port to scan, --open tells nmap to only show open ports, -n disables DNS resolution (saves time), and -oG - outputs the results in grepable format to stdout.

This is an example of the output:

Host: 1.2.3.4 () Status: Up

Host: 1.2.3.4 () Ports: 25565/open/tcp//minecraft//Now, we have a list of IP addresses with port 25565 open, and we can ping them with the SLP request.

Storing the results

To store the results, I used Elasticsearch. It might be overkill, but it allowed me to do full-text searches on MOTDs and filter by version, country, etc.

However, I didn’t want to write to Elasticsearch directly from the scanner, as it would slow it down and make it more complex.

So instead, I wrote the results to local JSON Lines (JSONL) files, and then used a separate worker to insert them into Elasticsearch.

This also allowed me to resume scans if Elasticsearch went down, and it made the scanner more resilient.

The worker would read the JSONL files and insert them into Elasticsearch using the _bulk API.

Here’s an example of the JSON document stored in Elasticsearch:

{

"ip": "1.2.3.4",

"port": 25565,

"timestamp": "2023-08-01T12:34:56Z",

"version": {

"name": "1.20.1",

"protocol": 763

},

"players": {

"max": 69,

"online": 1

},

"description": "Hello world!",

"favicon": "data:image/png;base64,...",

"enforcesSecureChat": false,

"latency": 42

}Note that I normalized some fields for easier filtering and searching (like description and version.name).

I also set up a retention policy to delete old data, as I didn’t need to keep it forever.

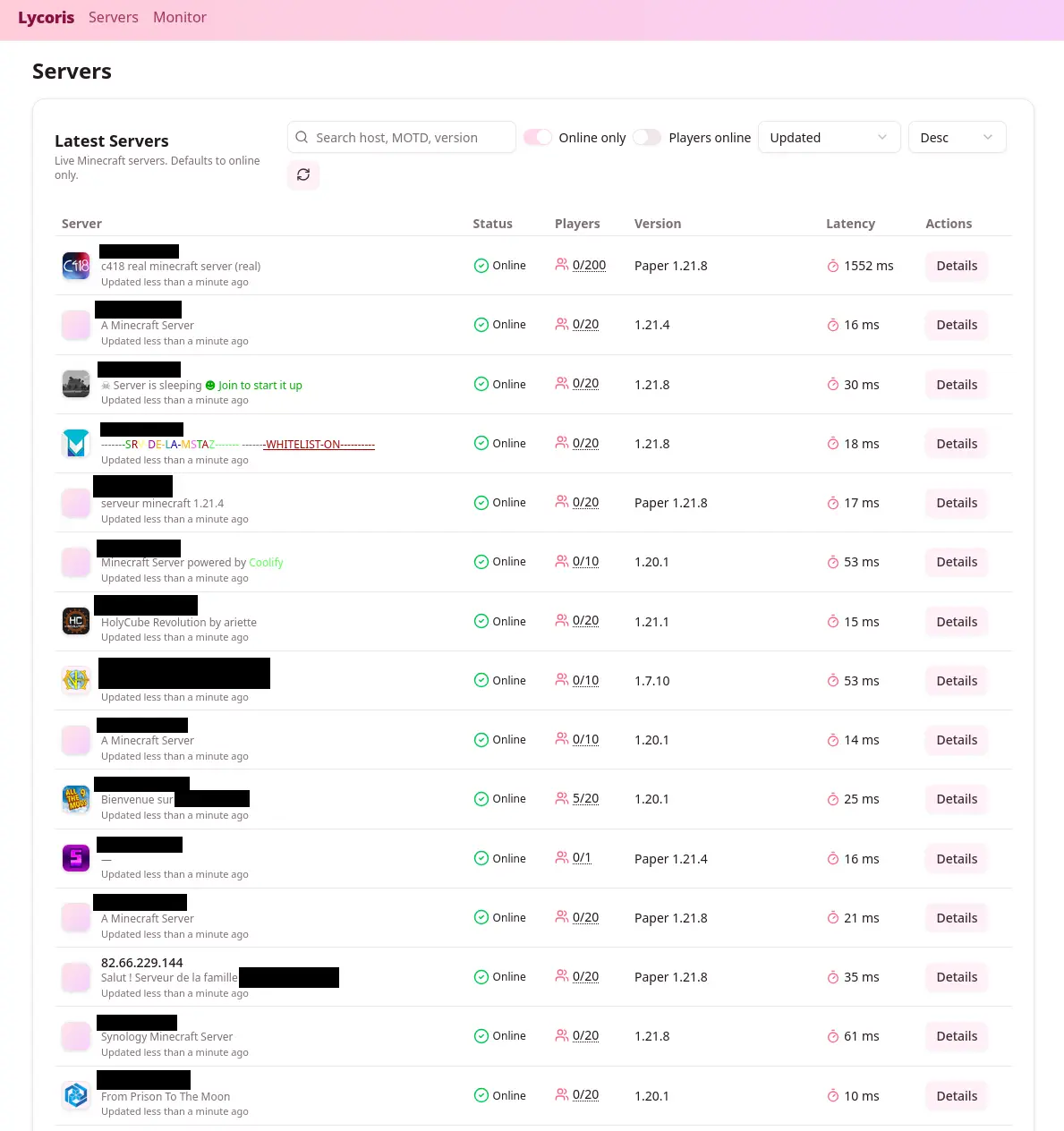

Visualizing the results

To visualize the results, I built a small web UI.

It was a simple table with the following columns:

- Favicon

- IP address

- Port

- Version

- MOTD

- Players online

- Max players

- Latency

It looked like this:

I also added a few filters and search options:

- Filter by version

- Filter by country

- Filter by player count

- Search in MOTD

Being a good netizen

Now, scanning IP ranges is not something you should do lightly.

It’s often against ISPs’ terms of service, and it can be considered intrusive.

So I made sure to be as polite as possible:

- I limited the scan rate to about 100 requests per second

- I added jitter and exponential backoff

- I used a token bucket to limit the global rate across multiple workers

- I respected block requests

Anyway, if you want to run mass scans like that, avoid doing it too fast or too regularly. My project ran for only a dozen hours to index a few million IP addresses from multiple ISPs in France.

What did I find?

Now that we have a lot of data, what did we find?

I scanned about 3 million IP addresses and found about 10 000 open Minecraft servers.

I then manually connected to about 200 servers.

Some of them had a whitelist, but I was able to connect to a few.

Most of them were small servers for friends, but some were more interesting.

A kid asked me for an autograph

On one server, a 14-year-old asked who I was. I watched in spectator while he built something, then he handed me a sign and asked for an autograph.

It made my day.

I got doxxed live (kind of)

I joined a small server with about five players. Someone insisted I share my Discord or get banned. After I joined their Discord, one guy got weirdly hostile and decided I must be a dangerous hacker.

He dug up old Minecraft usernames and confidently announced my “real name,” which was actually a completely unrelated person from Portugal. Meanwhile my actual name was linked on my GitHub profile.

Internet detective work at its finest.

I met an incel

Two students were playing. We chatted, then one started flirting, I declined, and he invited me to a private Discord.

He added that as a woman I might not fit in since it was only computer engineering students.

The funny part is that my Discord profile already says I build software for a living.

My school works hard to normalize women in tech.

Most of the time this kind of thing rolls off me. This time it felt gross.

Gamer grandpa

I found someone moving around awkwardly and not replying in chat. I crafted signs and explained how to chat.

He was 60 and had made a server to play with his grandson while learning. I told him to add a whitelist.

He added me to it so I could return, which I never did, but it was very wholesome.

Cool builds

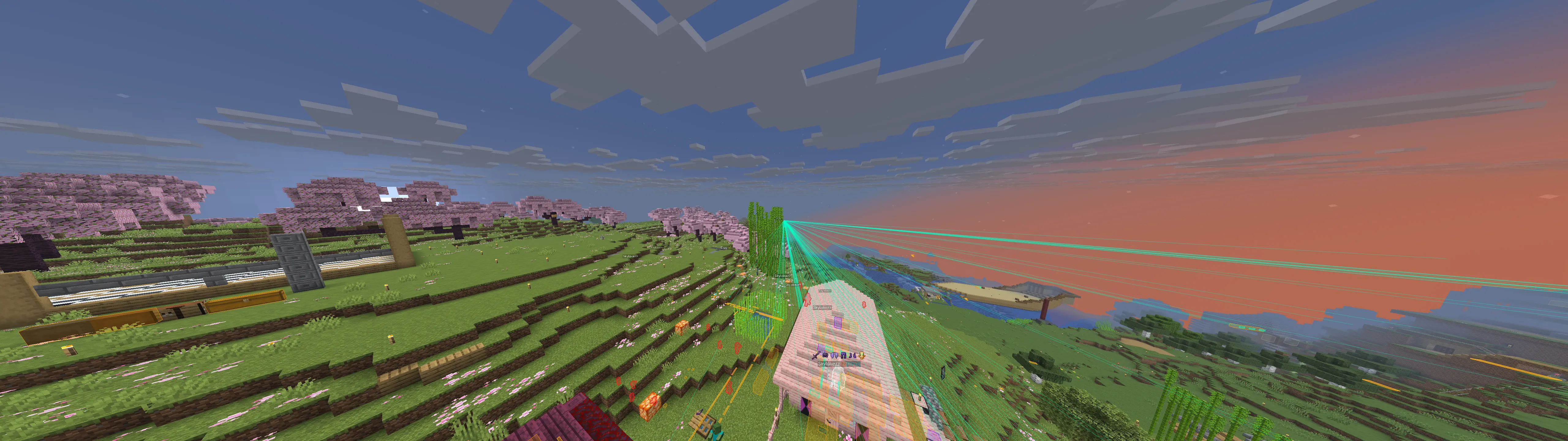

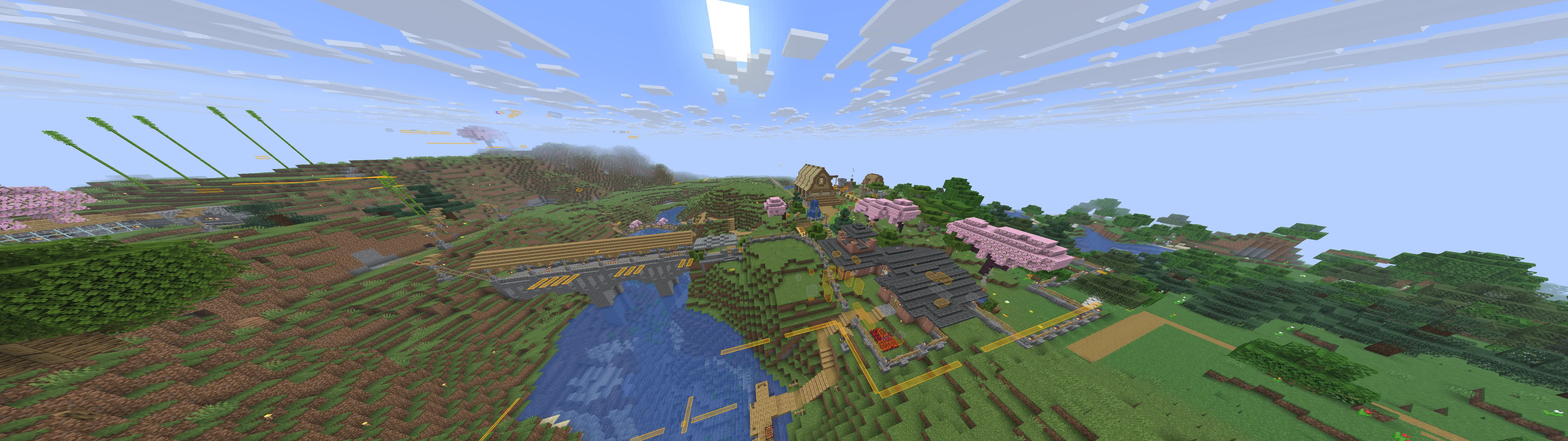

Here are a few builds I stumbled upon. Ignore overlays, I had cheats on.