Scanning IP ranges to find friends

One event led me to write an IP range scanner to find Minecraft servers.

summary

- A friend noticed a strange login on his Minecraft server, we traced it to a school IP via Shodan.

- Curious, I built my own scanner:

whoisfor IP ranges =>nmapfor open port 25565 => Minecraft Server List Ping => store JSON => Elasticsearch => React UI. - Scanned ~3 million IPs => found ~10 000 servers => joined ~200.

- Met a 14-year-old fan, a confused grandpa, and a few weird encounters.

- Lesson: scan gently, respect networks, and remember there’s a person behind every open port.

table of contents

How it started

A friend saw a strange login on his Minecraft server from what looked like a home IP. A quick look on Shodan showed it belonged to a local high school. Curious, we dug around, tried to find who it was, and eventually discovered (through some ethically questionable sleuthing) his name and email. I wrote to him, he replied, explaining he found the server through Shodan. We talked later about tech and security. Wholesome.

It reminded me of my own teenage curiosity, so I decided to build my own IP range scanner to find Minecraft servers.

How the scanner works

whois doesn’t just work on domains, it also returns IP ranges and ownership info. For each range, I used nmap to find hosts with port 25565 open:

nmap -p 25565 --open -n -oG - <IP_RANGE>Each open host gets a Minecraft Server List Ping (SLP). It’s a short handshake that returns version, players, MOTD, favicon, and latency. I use a Go library to automate it and record results.

Example response:

{

"version": { "name": "1.21.8" },

"players": { "online": 3, "max": 20 },

"description": "My survival server!"

}Storing and visualizing

The scanner writes results to local JSONL files, then a worker bulk-inserts them into Elasticsearch using _bulk.

Settings:

- Monthly rolling indices

- 90-day retention

- Compression and shallow mappings

Sample document:

{

"ip": "192.168.42.52",

"port": 25565,

"version": "1.21.8",

"players": { "online": 3, "max": 20 },

"description": "My survival server!",

"latency": 42

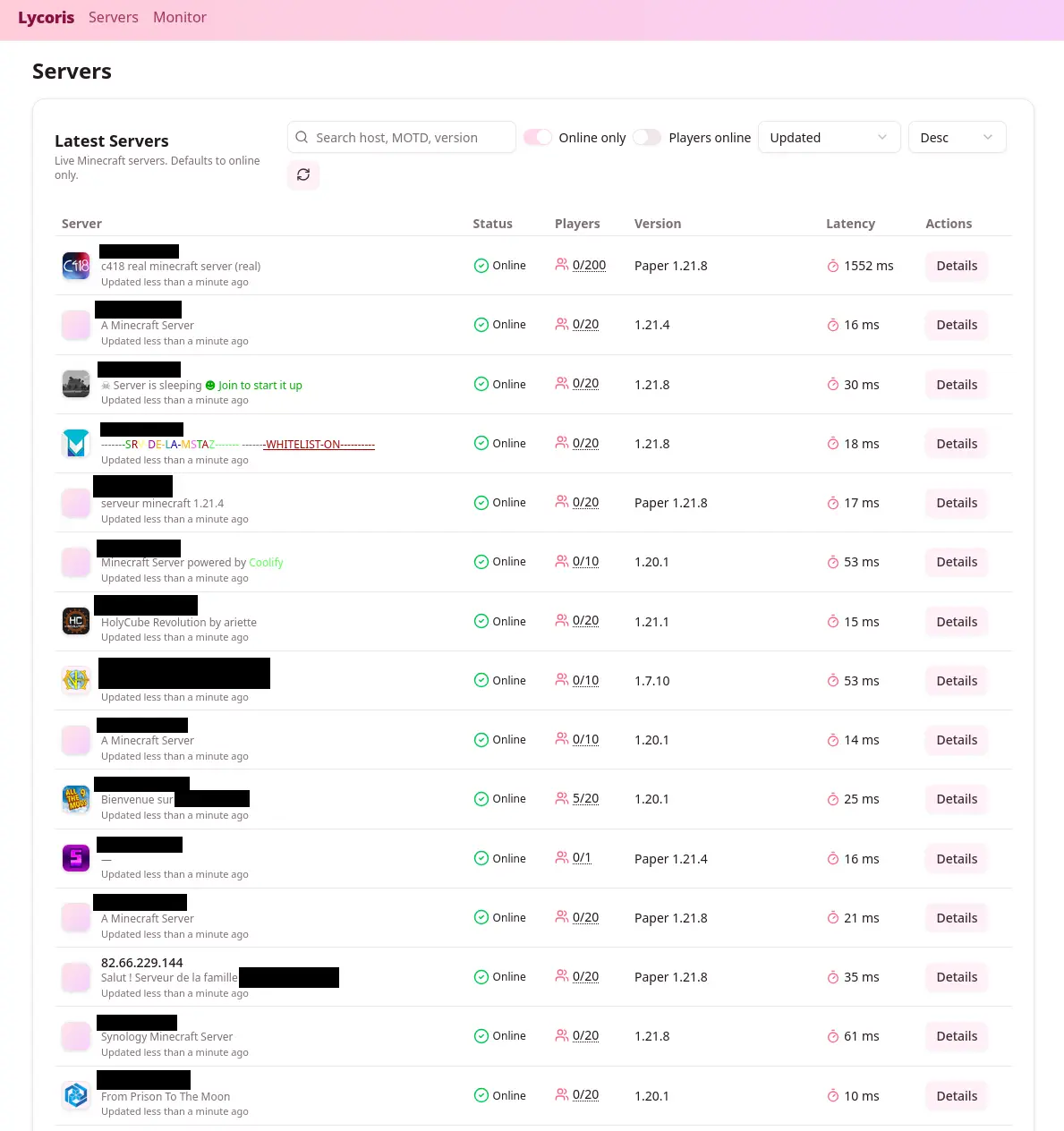

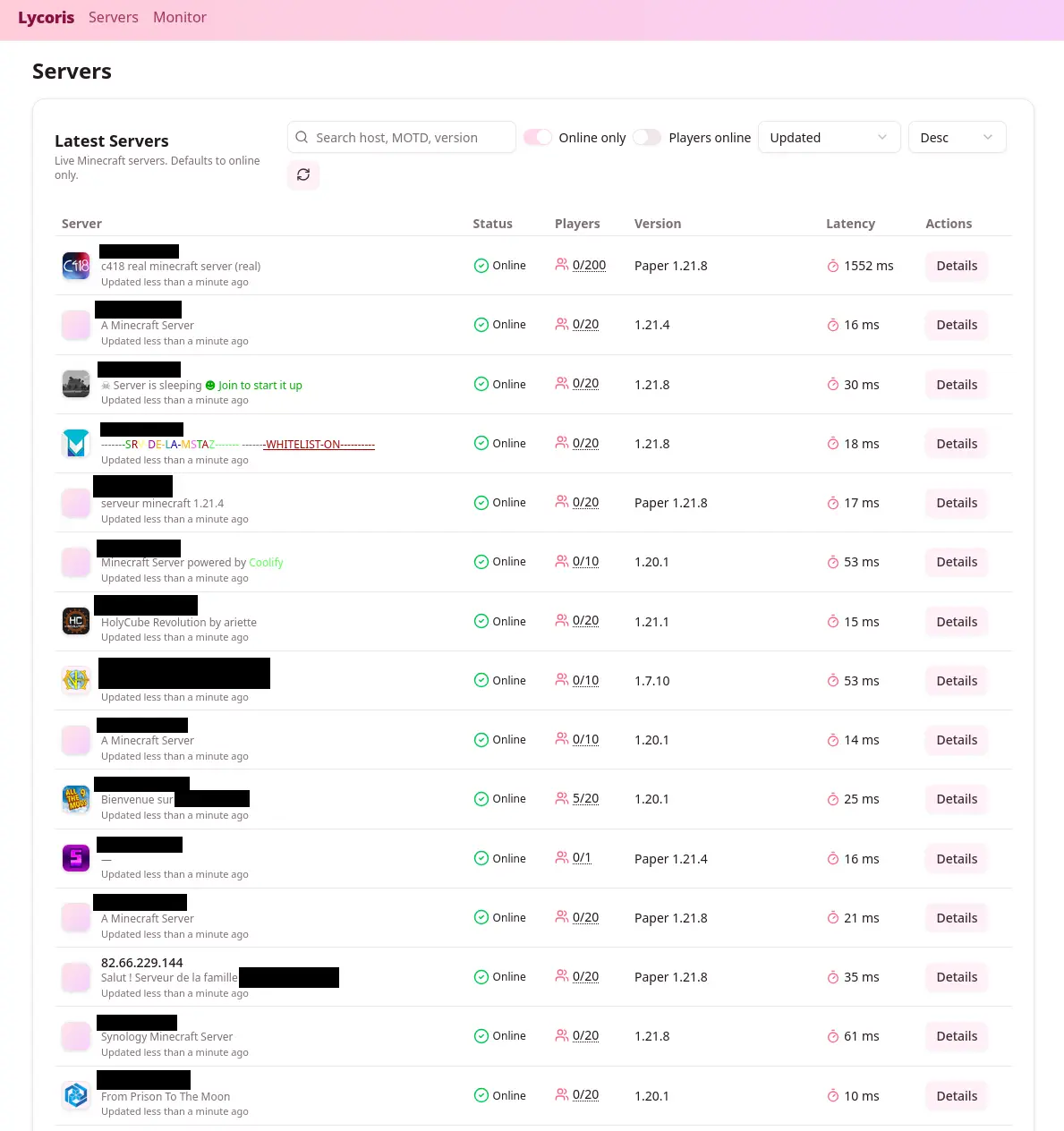

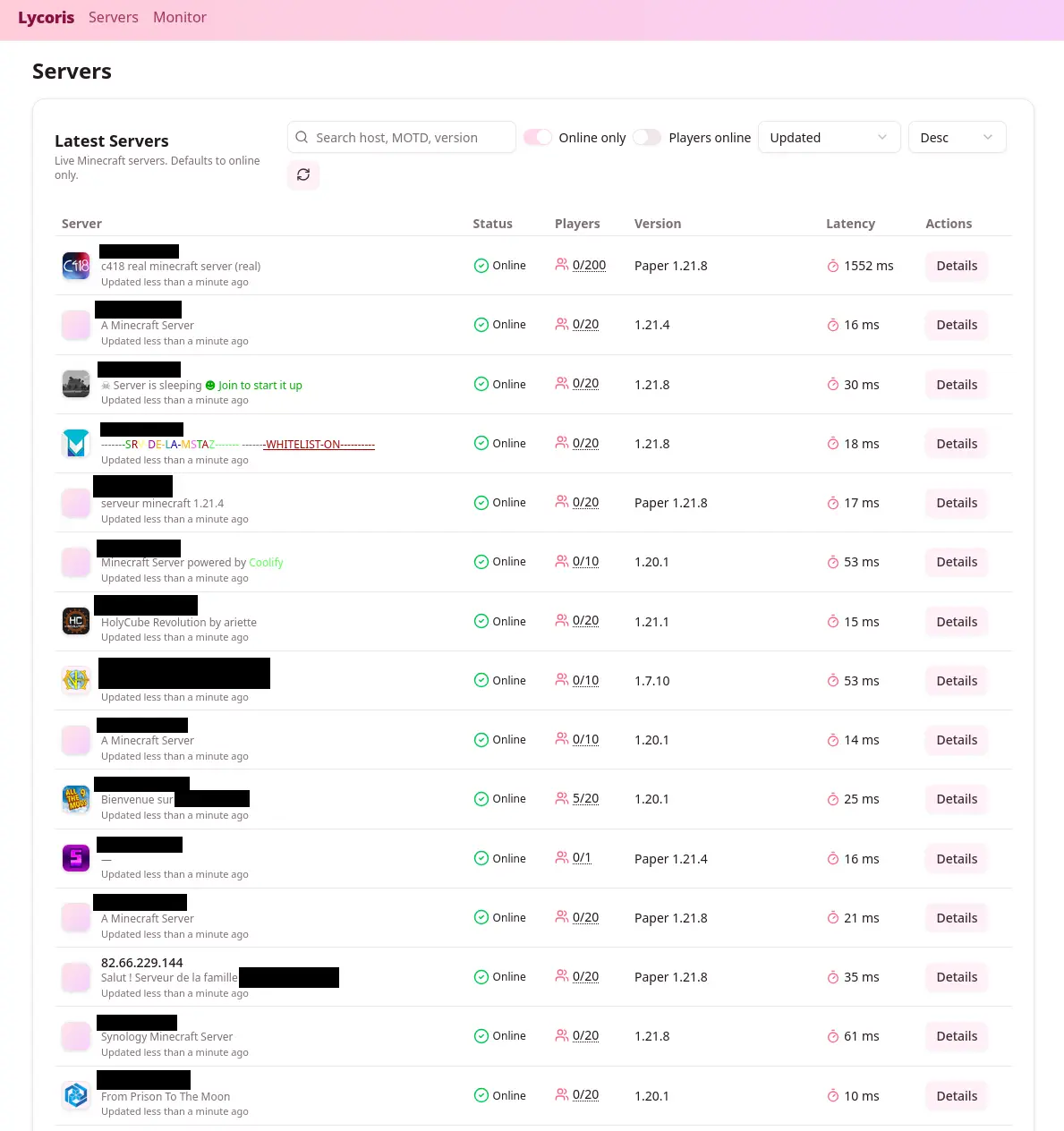

}The front-end is a small React table showing favicon, version, MOTD, players, and latency:

Staying polite

Mass scanning can be noisy. I kept it around 100 probes per second with jitter, exponential backoff, and a Redis token bucket across workers. The run lasted about 12 hours across a few French ISPs.

Results

- ~3 million IPs scanned

- ~10,000 servers found

- ~200 visited manually

Most were small friend servers. Only a few had proper permissions set.

Stories

A kid’s idol

A 14-year-old asked me for an autograph inside Minecraft. I signed his world.

Wrong “doxx”

Another group tried to expose my “real name” and ended up finding a random guy from Portugal. My actual info was on GitHub.

Gamer grandpa

A 60-year-old learning Minecraft to play with his grandson. I taught him to whitelist his server. Extremely wholesome.

Cool builds

Takeaway

The setup is simple: whois => nmap => SLP => JSONL => Elasticsearch => React UI.

The fun part wasn’t the data, it was the people behind each open port. Scan slow, be respectful, and stay curious.

How it started

A friend who runs a Minecraft server noticed a strange login from what looked like a residential ISP. A quick check on Shodan showed that the same IP hosted a local high school website. We assumed it was a student who found the server and tried to connect.

We tried to figure out who it was. NameMC was a dead end. Searches across Google, Bing, DuckDuckGo, and Yandex pointed to a chess.com account. Sherlock matched the username to a few other platforms but nothing identifying. In a last and admittedly unethical attempt, we checked leaked databases and found a first name, last name, and email. The Minecraft IGN turned out to be a pun on his real name.

So I emailed him. He replied the next day. He had used Shodan to find open Minecraft servers on port 25565 and was surprised I tracked him down. We moved to Discord, talked about CS, cybersecurity, and programming. It was wholesome, and it reminded me of the kind of curious scanning I did as a teenager. This time I wanted to do it properly and build an IP range scanner for Minecraft servers.

Scanning ranges

Most people use whois for domains. It also works on IPs and returns allocation info from RIPE/ARIN and the netblock. For example, whois 8.8.8.8 shows a /24 block owned by Google.

With a range in hand, I pre-filtered with nmap to avoid hitting every host with a Minecraft request:

nmap -p 25565 --open -n -oG - <IP_RANGE>Any host with port 25565 open gets a Minecraft Server List Ping (SLP). Since Java Edition 1.7, the client performs a short handshake, a status request, and receives a JSON response with version, players, MOTD, favicon, and a few flags. I use a maintained Go library to do the handshake and status call, and I record latency.

Example status JSON:

{

"version": { "name": "1.21.8", "protocol": 772 },

"players": {

"max": 20,

"online": 1,

"sample": [{ "name": "fake_username", "id": "0199d8c2-e4ab-79c9-ac5c-488688f041e0" }]

},

"description": { "text": "Hello, world!" },

"favicon": "data:image/png;base64,<data>",

"enforcesSecureChat": false

}Storing results

Scanning a few million IPs produces lots of tiny JSON events. I do not write directly to Elasticsearch while scanning. The scanner writes to local JSONL files first, then a separate worker bulk-inserts into Elasticsearch using the _bulk API in batches of about 1000 docs. This keeps the scanner resilient if Elasticsearch goes down, improves throughput, and makes it easy to resume.

To keep Elasticsearch under control:

- One index per month

- Retain about 90 days of old data

- Use

best_compression - Keep mappings shallow, especially

players.sample

Final document shape:

{

"ip": "192.168.42.52",

"port": 25565,

"timestamp": "2025-09-06T21:35:11Z",

"version": { "name": "1.21.8", "protocol": 772 },

"players": {

"online": 3,

"max": 20,

"sample": [

{ "name": "Steve", "id": "..." },

{ "name": "Alex", "id": "..." }

]

},

"description": "My survival server!",

"favicon": "data:image/png;base64,...",

"latency": 42

}Later, I can enrich with IP-to-ASN and country to answer questions like where servers live and which ISPs host the most.

UI and API

The UI is a simple React table that is good enough to browse results:

- Favicon

- Game version

- MOTD (description)

- Players online

- Total slots

- Latency

API endpoints:

GET /api/servers/latest?query=&onlineOnly=&playersOnly=&sort=&order=&page=&size=GET /api/servers/:host/:port/historyPOST /api/scanfor ad-hoc hosts and CIDRs

Here is what the table looks like:

Being a good netizen

Mass scanning is often against ToS and can be noisy. I kept the rate at about 100 probes per second with jitter and exponential backoff. When I ran multiple workers, I used a Redis-backed token bucket so the global rate stayed civil. A TCP pre-filter avoids SLP attempts on closed ports.

If you try anything similar, scan slowly, avoid repeated hits, and respect block requests. My project ran for about a dozen hours and covered a few ISPs in France.

Results at a glance

- About 3,000,000 IPs scanned

- About 10,000 Minecraft servers found

- Logged into about 200 servers

Most were small friend servers. Some had a whitelist. Only a handful had permissions set correctly so a random player could not interact with blocks.

Anecdotes

I was a kid’s idol

On one server, a 14-year-old asked who I was. I watched in spectator while he built something, then he handed me a sign and asked for an autograph. I signed his world. It made my day.

I got doxxed live (kind of)

I joined a small server with about five players. Someone insisted I share my Discord or get banned. After I joined their Discord, one guy got weirdly hostile and decided I must be a dangerous hacker. He dug up old Minecraft usernames and confidently announced my “real name,” which was actually a completely unrelated person from Portugal. Meanwhile my actual name was linked on my GitHub profile. Internet detective work at its finest.

I met an incel

Two students were playing. We chatted, then one started flirting, I declined, and he invited me to a private Discord. He added that as a woman I might not fit in since it was only computer engineering students. The funny part is that my Discord profile already says I build software for a living. My school works hard to normalize women in tech. Most of the time this kind of thing rolls off me. This time it felt gross.

Gamer grandpa

I found someone moving around awkwardly and not replying in chat. I crafted signs and explained how to chat. He was 60 and had made a server to play with his grandson while learning. I told him to add a whitelist. He added me to it so I could return, which I never did, but it was very wholesome.

Cool builds

Here are a few builds I stumbled upon. Ignore overlays, I had cheats on.

How it started

It all started when a friend of mine who runs a Minecraft server checked the logs and noticed that someone had logged in from an IP address that looked like it belonged to a residential ISP. Curious, we decided to investigate further. When we looked up the IP on shodan.io, we found that it hosted websites for a local high school. This piqued our interest, and we thought it was just a student who had installed Minecraft on a school computer, used Shodan to find the server, and logged in.

Finding out who it was

Then we wondered if there was a way to find out who it was. Looking up his IGN on NameMC didn’t yield any results, so we searched on Google, Bing, DuckDuckGo, and Yandex. We found a chess.com account. He played against his friends, but nothing else.

Using Sherlock, we were able to find more accounts associated with the same username across various platforms but nothing that could help us identify him.

That’s when I had the idea to look in leaked databases, it was a bit desperate (and very unethical) and I didn’t have high hopes, but it worked! We found a first name, a last name, and an email address. Funnily enough, we realized right after that his Minecraft username was a pun based on his real name (and a pretty funny one at that).

So I sent him an email! (translated from French)

Hello [Name]!

I'm reaching out to ask if it was you who connected to my Minecraft server under the username [IGN]?

I'm really curious to know how you managed to get on, especially since it looks like you connected from your high school.

It would be pretty cool if you found it by scanning an IP range!

I hope I'm not barking up the wrong tree here.

Have a great day!

~mollyAnd the next day.. I got a reply!

Hey Molly!

It was probably me who connected to your Minecraft server, since my username is [IGN].

I found your Minecraft server through a website called Shodan (if you don't know it => https://www.shodan.io/).

It's a site that scans the entire internet to find open ports (for example, port 25565 in the case of your Minecraft server).

And I have a question: how did you find my email and that I'm in high school? (From my IP? My Minecraft account?)

Also, could you send me the server's IP again? It's possible I don't have it anymore.

You were on the right track!

And I was a bit shocked to get this email, nice job!

Have a great day!

[Name]We talked a little bit then by email, then Discord and he asked us a lot of questions about computer science, cybersecurity and programming in general, this was extremely wholesome.

This entire experience made me realize that this was the kind of thing I also did for fun when I was a teenager, except that I remained anonymous.

So I decided to build an IP range scanner to find Minecraft servers !

How does it work?

Before talking about the implementation details, let’s go over the general idea.

RIPE IP ranges

I learned recently that the whois command on Linux can not only be used on domain names but also on IP addresses. It queries the RIPE database to find out who owns a given IP address, and in what IP range it is located.

For example, if we run whois 8.8.8.8 (Google’s public DNS server), we get the following output:

NetRange: 8.8.8.0 - 8.8.8.255

CIDR: 8.8.8.0/24

NetName: GOGL

NetHandle: NET-8-8-8-0-2

Parent: NET8 (NET-8-0-0-0-0)

NetType: Direct Allocation

OriginAS:

Organization: Google LLC (GOGL)

RegDate: 2023-12-28

Updated: 2023-12-28

Ref: https://rdap.arin.net/registry/ip/8.8.8.0

OrgName: Google LLC

OrgId: GOGL

Address: 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway

City: Mountain View

StateProv: CA

PostalCode: 94043

Country: US

RegDate: 2000-03-30

Updated: 2019-10-31

Comment: Please note that the recommended way to file abuse complaints are located in the following links.

Comment:

Comment: To report abuse and illegal activity: https://www.google.com/contact/

Comment:

Comment: For legal requests: http://support.google.com/legal

Comment:

Comment: Regards,

Comment: The Google Team

Ref: https://rdap.arin.net/registry/entity/GOGL

OrgTechHandle: ZG39-ARIN

OrgTechName: Google LLC

OrgTechPhone: +1-650-253-0000

OrgTechEmail: [email protected]

OrgTechRef: https://rdap.arin.net/registry/entity/ZG39-ARIN

OrgAbuseHandle: ABUSE5250-ARIN

OrgAbuseName: Abuse

OrgAbusePhone: +1-650-253-0000

OrgAbuseEmail: [email protected]

OrgAbuseRef: https://rdap.arin.net/registry/entity/ABUSE5250-ARINWhat’s interesting here are the NetRange and CIDR fields, which tells us that the IP range for this address is 8.8.8.0 - 8.8.8.255 (or the 8.8.8.0/24 CIDR mask).

This means that any IP address within this range is owned by Google LLC.

So, I took my own IP address, ran whois on it, and decided to run nmap -p 25565 --open -n -oG - <IP_RANGE> on the resulting IP range to find any open Minecraft servers.

I then manually connected to the open servers, some of them had a whitelist, but I was able to connect to a few!

Getting a server’s status programatically

If you played Minecraft, you know that when adding a server to your server list you will be able to see the number of online players, total number of slots, an MOTD and an icon.

This is because upon loading your server list, your client will communicate with each servers you added using an interface called Server List Ping ****(**SLP**), it changed in the Java Edition 1.7 (late 2013). It’s a 3 steps communication that allows your client to fetch the server’s status.

Step 1: Handshake

Your client sends a Handshake packet with its state set to 1

+--------+-------------------+---------------------+-------------------+

| 0x00 | Protocol Version | Server Address | Server Port |

| VarInt | VarInt | String | Unsigned Short |

+--------+-------------------+---------------------+-------------------+

| Next State (VarInt) (1 for status, 2 for login, 3 for transfer) |

+----------------------------------------------------------------------+Step 2: Status request

Your client sends a packet with only a 0x00 in it.

Step 3: Status Response

Finally, you receive this JSON object:

{

"version": {

"name": "1.21.8",

"protocol": 772

},

"players": {

"max": 20,

"online": 1,

"sample": [

{

"name": "fake_username",

"id": "0199d8c2-e4ab-79c9-ac5c-488688f041e0"

}

]

},

"description": {

"text": "Hello, world!"

},

"favicon": "data:image/png;base64,<data>",

"enforcesSecureChat": false

}source: https://minecraft.wiki/w/Java_Edition_protocol/Server_List_Ping

In code, I rely on a maintained Go library that performs the handshake => status => JSON flow and I record: version, players (online/max), MOTD/description, favicon (base64) and measured latency.

Storing the data

We’ll be scanning a few million IPs to start with, and we need a way to store each status response efficiently, query it, and make sense of it over time.

For this project, I chose Elasticsearch. It’s perfect for this kind of data: JSON documents, large-scale ingestion, and flexible queries for historical tracking or analytics.

Final document structure

{

"ip": "192.168.42.52",

"port": 25565,

"timestamp": "2025-09-06T21:35:11Z",

"version": {

"name": "1.21.8",

"protocol": 772

},

"players": {

"online": 3,

"max": 20,

"sample": [

{ "name": "Steve", "id": "..." },

{ "name": "Alex", "id": "..." }

]

},

"description": "My survival server!",

"favicon": "data:image/png;base64,...",

"latency": 42

}This can be enhanced with IP-to-ASN databases to see how many servers there are in X country, or which ISP hosts the most Minecraft servers.

Ingestion Pipeline

Instead, it writes the results to local JSONL files first, to avoid overloading Elasticsearch during long scans. Then, a separate ingestion script (a Python or Go worker) reads these JSONL files and bulk-inserts them into Elasticsearch using the _bulk API, in batches of 1000 documents.

That approach:

- Decouples scanning from storage (if Elasticsearch goes down, the scan continues)

- Improves performance (batch insertions are much faster)

- Keeps everything fault-tolerant and easy to resume

Index lifecycle

To avoid Elasticsearch turning into a RAM-eating monster after a few million documents, I added:

- A rolling index policy (one index per month)

- A retention period of ~90 days for old data

- Compression (

best_compressioncodec) - Limited mapping depth for nested fields like

players.sample

This makes long-term scans feasible even on modest hardware.

Rendering the data

For that, a simple table in React will be enough, in this table we will render these fields:

- Favicon

- Game version

- MOTD (referred as description above)

- Player count

- Total slots

- Latency

Here’s what it looks like in the end:

API

The UI consumes a tiny REST API:

GET /api/servers/latest?query=&onlineOnly=&playersOnly=&sort=&order=&page=&size=GET /api/servers/:host/:port/history, time series for a given server.POST /api/scan, ad-hoc scan for providedhostsand/orcidrs.

Being a good Netizen

Doing these kind of things on Internet is often questionable, whether you need it or not, it is often not allowed by ISP and other cloud providers.

I was too lazy to read my ISP’s Terms of Use, but I believe that not spamming the entire network with TCP connections everywhere is important.

I limited myself to ~100 probes per second with jitter and exponential backoff on failures; when needed I enable a global token-bucket (via Redis) to keep the rate civil across multiple workers/instances. The TCP pre-filter also helps avoid unnecessary SLP attempts on closed ports.

Anyway, if you want to run mass scans like that, avoid doing it too fast or too regularly. My project ran for only a dozen hours to index a few million IP addresses from multiple ISPs in France.

Results

Out of +3 millions IPs scanned, I found 10k Minecraft servers, and logged on ~200 of them.

These Minecraft servers were mostly the kind you’d run during holidays with your friends when you were younger. Some had a whitelist, some didn’t, and among those that didn’t, only two had proper permissions set up so I couldn’t interact with blocks.

Funny anecdotes

I was a child’s idol

One of the servers I logged into was owned by a 14-year-old. Like most people I stumbled upon while connecting to random servers, he asked who I was, etc. He was building… something? I asked if I could be in spectator mode to see what he was building (he accepted). Later, he put me back in survival mode and asked me for an autograph (while handing me a sign), so I signed his world!

I got doxxed live (kind of)

Same thing happened again, I logged into a small server with maybe five players. Someone asked who I was, I joined their survival world and started speedrunning the dragon without talking much. Then they asked for my Discord (or they’d ban me!).

They added me as a friend and invited me to their server.

My Discord profile has my website and GitHub linked, nothing too special. For some reason, one of them got really hostile toward me (and I still don’t understand why, I was just playing the game). Then he found out I was a software engineer with some cybersecurity work I had on my website and instantly decided I must be some kind of dangerous h4ck3r™.

I tried to explain that I was just a bored girl scanning IPs to find open Minecraft servers.

And that’s where it got funny: he started digging up my old Minecraft usernames, found a completely unrelated person from Portugal, and began spreading my “real name” on his Discord, complete with random racist slurs and pictures of this poor Portuguese guy.

Ironically, all he had to do was click on my GitHub profile to find my actual name.

I met an incel

A bit like the previous story, logged in, bla-bla-bla, two guys were playing on the server (I later learnt they were ~20 years old).

Told them the exact same story again, just a bored girl doing nerd things. One of them started hitting on me (which was objectively pretty cringe), they added me on Discord and I told him I wasn’t interested, so he naturally started being a bit hostile and he wanted to invite me on a Discord server he had with his friends.

He told me it was a Discord server with only computer engineering students, and that, you know, as a woman, I might not really fit in, which is kind of funny, considering he could’ve just looked at my Discord profile and seen that’s literally what I do for a living.

I’m usually not too sensitive to this kind of thing, it mostly goes over my head or even makes me laugh sometimes, but this time I actually found it a bit revolting. My school puts a lot of effort into normalizing women in tech, and I was genuinely happy to contribute to that in my own way back then. It’s just a shame that some people (even jokingly) still think or say things like that.

Gamer grandpa

One of the most wholesome things that happened is finding someone, confusedly moving in his world, he didn’t answered me in the chat so I crafted and gave him signs and proceeded to explain him how to use the chat.

He told me he was 60 years old and had created this server to play with his grandson while learning the game. I told him to add a whitelist on his server, and he added me to it so I could rejoin whenever I wanted (which I never did), surprisingly wholesome.

Cool builds

To finish this blog post, here are some cool builds I found on multiple servers! (Ignore the overlays, I had cheats on.)